A New Democracy

Huey Long’s election in 1928 ushered in a democratic revolution in Louisiana, giving average citizens a stake in their government for the first time in the state’s history. By turning out the aristocratic ruling establishment and repealing the poll tax, Long enabled more than a quarter million citizens the opportunity to vote, nearly doubling the size of the electorate the year following his assassination.

Prior to Long’s election, Louisiana’s electoral system was designed to keep poor people from voting, thus maintaining a strict division between the ruling upper class and their lower class ‘subjects’. The poll tax ensured that only citizens of sufficient wealth could vote. Before elections, voters were required to pay a dollar fee at the parish courthouse and receive a receipt. On election day, only voters presenting receipts for two consecutive years could cast a ballot. If you could not present two correct receipts, you were effectively disenfranchised for the next three years.

Most citizens could not afford to spend the dollar – a day’s wage for the average sawmill worker – or take the day off from work to travel to the parish seat to pay the tax. Property owners were the only citizens likely to pay the poll tax, because they could afford the fee and had to travel to the courthouse anyway to pay their annual property taxes. In a particularly cruel twist, the poll tax was due at Christmastime, adding another disincentive for poor citizens to seek the privilege of voting.

Participation in the legislative process was firmly restricted to the wealthy class. For generations, Louisiana politics had been dominated by three factions that enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship – the planter class, the New Orleans political machine known as the ‘Old Regulars’, and the big businesses that made money from state resources. This alliance represented the top 5% of the population and paid little attention to the plight or needs of the impoverished masses.

Political corruption and bribery was rampant. Legislators were unsalaried and received a per diem payment for each day the legislature was in session. House members received $10 a day and Senators received $20 a day. The Lt. Governor also received a per diem, and only the governor received a salary – $7,500 a year and a free residence. Traditionally, the governor bought his support through the political patronage system, promising state jobs and lucrative contracts to supporters. Big corporations usually resorted to offering good jobs and cash in exchange for friendly votes.

Huey Long promised voters a fairer shake from their state government and ridiculed the ruling establishment for their self-serving deals and indifference to the public’s plight. He pledged to provide free education, good roads, and a decent standard of living. Average citizens seized the opportunity to elect one of their own to the governorship and swept Long into office by a large plurality, beating his nearest opponent by 45,000 votes in a three way race.

The resulting sea-change in Louisiana politics was historic. The old political system was replaced by a new division between ‘pro-Longs’ and ‘anti-Longs’, a bitter feud between the conservative old guard and progressives. Over the next seven years, Long and his successors battled opponents to deliver his promises – good roads, modern bridges, education, health care, lower utility rates, reduced taxes and other public services.

Long won support for his agenda by using the political patronage system to his advantage, installing supporters in all levels of government and winning legislative support with favors and threats. In the face of fierce opposition, Long wrestled power away from enemies and created a mighty political machine of his own. Opponents characterized Long as a power-hungry dictator. Supporters countered that Long was a true champion of the people, using the governor's clout to provide for the common good.

Long did not live to enjoy one of his greatest victories, the elimination of the poll tax, which occurred shortly before his assassination in 1935. By the 1936 election, more than 278,000 citizens registered to vote for the first time.

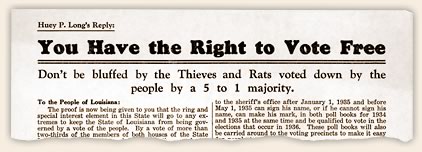

This Huey Long circular, 'You Have the Right to Vote Free', was distributed throughout Louisiana to encourage citizens to exercise their new right to vote without paying the dollar poll tax. Long used circulars like these to inform the public of their rights and to promote his programs, because the state's newspapers were aligned against him and often printed false information.

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

- Previous page

- Economic Reform

- Next section

- Perspectives

Courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana

In breaking the monopoly of the powerful ruling elite in Louisiana, the Bourbons, Huey Long’s victory was not that of one man but a triumph of monumental proportions for the mass of Louisiana citizens.”

— Prof. Sue Eakin

The Poll Tax

In 1928, voters were required to have paid $2 in poll taxes at the courthouse prior to the election. This represented two days wages for many poor laborers and is the equivalent of $24 dollars today.

When Huey Long managed to repeal the poll tax in 1935, more than a quarter million citizens registered to vote by the following year. The electorate expanded from 365,000 registered voters in 1927 to 643,590 voters in 1936, an increase of 76 percent. Long was killed in 1935 and did not live to see the results of the poll tax repeal.