Senator

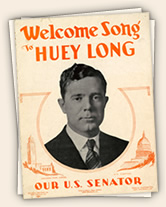

In 1930, Huey Long ran for the U.S. Senate, characterizing the race as a referendum on his policies to strengthen his position as governor. He won easily but left the Senate seat vacant until he could install a loyal successor to continue his reform agenda in Louisiana. In Washington, Huey became a national force with his “Share Our Wealth” movement, which threatened to siphon Democratic support from the re-election of President Franklin Roosevelt.

In the Louisiana legislative session following the impeachment debacle, opponents blocked Huey’s proposals for a major road-building initiative and the construction of a modern capitol building in Baton Rouge to house all departments of government. Huey countered by announcing he would run for the U.S. Senate in the fall of 1930 as a referendum on his programs. He promised to resign the governorship if he lost the Senate race; but a win would signal to the legislature where their constituents stood.

Cyr’s Debacle

Lt. Governor Paul Cyr, a Long opponent, claimed that Huey vacated his governorship upon his election to the U.S. Senate. In the fall of 1931, Cyr staged a “coup d’etat” and had himself sworn in as governor, claiming a Baton Rouge hotel as the new seat of government.

Huey responded that he was still governor because he had not taken the oath of office as Senator. He called out the National Guard to secure the capital city and declared that Cyr had vacated his office by taking the oath for the governorship.

The courts agreed, and under state rules the president of the state senate, Alvin O. King, became Lt. Governor. With his friend set to succeed him, Long resigned as governor and left for Washington.

Long soundly defeated incumbent Senator Joseph E. Ransdell, but he left the Senate seat vacant for nine months for fear that Lt. Governor Paul Cyr would roll back his reforms once Huey left for Washington. (In response to critics, Long quipped that the seat had already been vacant 32 years under Ransdell.) After a bungled attempt by Cyr to seize the governorship, Long ally Alvin O. King became Lt. Governor, allowing Huey to take his seat in the Senate.

Huey continued to be in effective control of Louisiana after the next gubernatorial election, when he successfully campaigned for Oscar K. Allen, a childhood friend and loyal supporter, who followed Long’s instructions in the governor’s office. He frequently traveled back to Baton Rouge to push his programs through the legislature, including abolishing the poll tax and creating a homestead tax exemption for personal property.

The Great Depression

Huey believed that the Great Depression was the result of the tremendous disparity between the wealthy and the poor. He charged that the richest five percent of the population controlled 85 percent of the nation’s wealth. There just was not enough to go around. By 1934, nearly half of all Americans lived in poverty, earning less than $1,250 annually.

In Huey’s view, capitalism had run amuck and the vast majority of the population was suffering as a result of corporate greed. The nation was stuck in a vicious cycle in which people had no money to put into the economy, and jobs were drying up because there was no commerce. One in four breadwinners was out of work, and more than a million men roamed the country in search of work.

Surpluses of food and textiles were destroyed for lack of buyers, while millions lost their worldly possessions and lived on the brink of starvation.

Huey arrived in Washington in January 1932. As the Great Depression worsened, he made impassioned speeches in the Senate charging a few powerful families with hoarding the nation’s wealth. Noting that 95 percent of the nation’s wealth was held by only 15 percent of its people, Huey urged Congress to address the inequality that he believed to be the source of the mass suffering. How was a recovery possible when twelve men owned more wealth than 120 million people?

In 1934, Huey unveiled a program of reforms called Share Our Wealth to redistribute the nation’s wealth more fairly, capping personal fortunes at $50 million (later lowered to $5 - $8 million) and distributing the rest through government programs aimed at providing opportunity and a decent standard of living to all Americans. Huey believed his programs in Louisiana were effective in lifting people out of poverty, and he wanted to implement this philosophy nationally.

Huey accused both parties of selling out to big business at the expense of the American people. He became very unpopular with the political establishment in Washington and was labeled a “socialist,” “radical,” “demagogue,” and “dictator.” Soon the conservative national media joined the “anti-Long” bandwagon and echoed the negative portrayal of Huey from the Louisiana newspapers.

Huey countered the negative press by taking his case straight to the people through national radio broadcasts, speeches to large audiences, and the creation of his own newspaper, The American Progress. While Long’s pull-no-punches style won him few friends in Washington, his message struck a chord with average Americans. By the summer of 1935, Huey’s Share Our Wealth clubs had 7.5 million members nationwide, he regularly garnered 25 million radio listeners, and he was receiving 60,000 letters a week from supporters (more than the president).

In the presidential election of 1932, Huey had supported the candidacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, believing him to be the only candidate that shared his philosophy for wealth redistribution. Long played a critical role in securing the Democratic nomination for FDR and campaigned for him in the Midwest. However, Huey broke with Roosevelt when the new president failed to embrace his programs. Huey considered FDR’s first New Deal reforms to be woefully inadequate and threatened to run for president himself in 1936.

Courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana

- Previous page

- Impeachment

- Next page

- Presidential Candidate

Huey Long speaking at the 1932 Democratic National Convention in support of the nomination of Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana

The only difference I ever found between the Democratic leadership and the Republican leadership is that one of them is skinning you from the ankle up and the other, from the neck down.”

— Huey Long, from his famous speech, ‘High Popalorum and Low Popahirum’

Share Our Wealth

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

In a national radio address in February 1934, Huey Long unveiled a plan called Share Our Wealth, a program designed to provide a decent standard of living to all Americans by spreading the nation’s wealth among the people.

Long proposed capping personal fortunes at $50 million through a restructured federal tax code and sharing the resulting revenue with the public through government benefits. Later revisions included capping fortunes at $5 - $8 million, annual personal incomes at $1 million (or 300 times the average American income) and limiting inheritances to $5 million per individual.

Long’s program advocated free higher education and vocational training, pensions for the elderly, veterans benefits and health care, and a yearly stipend for all families earning less than one-third the national average income – enough for a home, an automobile, a radio, and the ordinary conveniences. Long also proposed shortening the workweek and giving employees a month vacation to boost employment, along with greater government regulation of economic activity.

A National Following

Huey was the first politician, other than President Roosevelt, to use national radio broadcasts to promote his ideas to a larger audience. After offering bills in the Senate, he purchased radio time with the National Broadcasting Company to explain his proposals to the American public, bypassing the usual filters and criticism of the conservative newspapers.

Huey developed a following of an estimated 25 million loyal listeners, who started 27,000 Share Our Wealth clubs across the nation. President Roosevelt used national radio speeches to connect with the public through his “fireside chats,” which were similar to the radio broadcasts Huey had used in Louisiana while he was governor to educate the public about his proposals.

A “Top Stop” for Tourists

Huey's Senate speeches became legendary, as he packed the public galleries. According to one Washington tourist guide, top stops were "White House, Monument, Capitol — and The Kingfish".

On June 12, 1935, Long launched a 15-hour one-man filibuster against a modification of the National Recovery Act (for being a giveaway to big business). Humorist Will Rogers once quipped, "Imagine 95 senators trying to out-talk Huey Long. They can't get him warmed up."