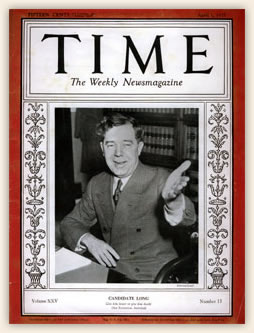

Presidential Candidate

Huey Long was poised to run for president in the 1936 election against Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He had risen to national prominence with his “Share Our Wealth” program, which swept the nation as the Great Depression worsened. Meanwhile, FDR adopted some of Huey’s ideas in order to “steal Long’s thunder,” while simultaneously moving to discredit him.

By 1935, Huey’s Share Our Wealth Society had over 7.5 million members in 27,000 clubs across the country. Long's Senate office was flooded with thousands of letters daily, prompting him to hire 32 typists, who worked around the clock to respond to the fan mail. As the nation’s third most photographed man (after FDR and celebrity aviator Charles Lindberg), Long was recognized from coast to coast simply as “Huey.” One national poll found Huey to be the most attractive man in America – ahead of Tarzan.

To Roosevelt, however, Huey was “one of the two most dangerous men in America.” (The other was Gen. Douglas MacArthur.) Roosevelt sought to undercut Huey’s clout by putting Huey’s enemies in charge of federal spending and patronage in Louisiana. He ordered unproductive investigations by the Internal Revenue Service and the FBI into Huey’s finances and other dealings. Huey was also the subject of the first nationwide political poll, used by the Roosevelt campaign to assess how great a threat a Long candidacy would be to the President’s re-election. According to Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley, Huey was polling up to 6 million popular votes and his appeal was nationwide.

FDR also moved to deflate Long’s appeal by incorporating some of Huey’s ideas as part of the Second New Deal, a more liberal version of his Great Depression reforms. For example, the Social Security system reflected Huey’s proposal for old-age pensions, the Works Progress Administration mirrored public works programs begun by Long in Louisiana, and the National Youth Administration reflected his student financial aid proposal. Other initiatives championed by Long and implemented by FDR included the National Labor Relations Board (rights of unions to organize, minimum wage and 40-hour work week), the Public Utility Holding Company Act (regulation of public utilities), the Farm Security Administration (assistance to farmers), and the Wealth Tax Act (graduated income and inheritance taxes).

Courtesy of the Long family

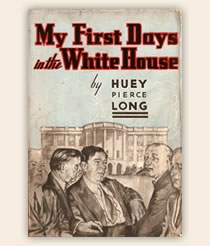

My First Days in the White House

To prepare the nation for his upcoming presidential bid, Huey wrote My First Days in the White House, the reflections of a President Long after his first 100 days in office. Written in 1935, the book was published in 1936 after Huey’s assassination.

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

- Previous page

- Senator

- Next page

- Assassination

Courtesy of the Louisiana Political Museum & Hall of Fame

They’ve got a set of Republican waiters on one side and a set of Democratic waiters on the other side, but no matter which set of waiters brings you the dish, the legislative grub is all prepared in the same Wall Street kitchen.”

— Huey Long

Huey & Hattie

A Senate First

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

In 1932, Huey exercised his political muscle to elect the widow of his friend, Arkansas Sen. Thad Caraway, to the U.S. Senate. Hattie Caraway was appointed to serve out the remainder of her husband’s term but was the underdog in the upcoming election. She faced six opponents, including a candidate supported by Senate Majority Leader Joseph Robinson, with whom Huey had frequently clashed.

Huey sympathized with Caraway and engineered an eight-day barnstorm of Arkansas. He and Caraway covered 2,100 miles and made 39 appearances together, drawing an estimated 200,000 Huey Long admirers to the Hattie Caraway bandwagon. One stunned political observer described Huey's whirlwind tour as "a circus hitched to a tornado".

With Huey’s endorsement, Caraway swept to an easy victory, becoming the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate. Ironically, Huey’s widow, Rose, would be the second woman elected to the Senate in 1936 after Huey’s assassination.