Economic Reform

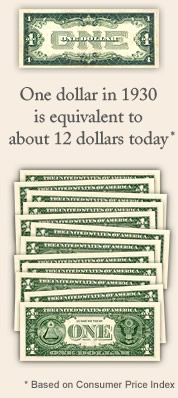

Huey Long transformed the economic reality in Louisiana from a system stacked against its rural poor citizens to a system that offered opportunity and tools for advancement. By 1936, Long’s programs and progressive policies saved the average Louisiana family more than $425 a year in daily living expenses (equivalent to $5,100 today). Coupled with free education and easier mobility, people on every step of the economic ladder received a chance to get ahead, especially the poor.

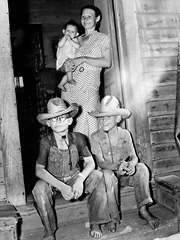

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

Prior to Huey Long’s administration, the cost of living in Louisiana was high for everyone, especially Louisiana’s poor majority. Individuals were required to pay for everything the state did not provide – education for their children, tolls for ferry crossings where no bridges existed, annual fees required for the privilege of voting, and taxes on every form of personal property.

The disenfranchised poor eked out a meager existence, doing without the necessities that would provide a better quality of life, and paying taxes every year for services they never received. To add insult to injury, unregulated utilities and businesses charged top dollar for basic goods and services. At the onset of the Great Depression, already desperate families risked losing what little they had.

Long shifted the public’s perception of what they should expect from their government. The state soon provided free education, roads, bridges, and infrastructure and reduced burdensome property taxes, fees, and utility rates. By 1936, the average family saved more than $425 a year in living expenses (or $5,100 today), which enabled hundreds of thousands of citizens to invest in a better future.

With the state providing free schools, buses, and textbooks, the average family with three children saved $30 a year on books alone (or $360 today). Individual parishes no longer taxed residents to maintain the few public schools that previously existed, and higher education tuition was reduced as the state’s public universities tripled enrollment.

The free hard-surfaced roads and bridges saved the average family $150 a year in tolls and ferries (or $1800 today). Reduced gas consumption and wear-and-tear saved car owners another $118 a year (or $1,416 today).

Personal property taxes were reduced by the ‘Homestead Exemption’, which eliminated taxes on every household’s first $2,000 of property. In 1928, most homes were worth less than $2,000, saving the average family $65 annually (or $780 today). Eighty percent of all homeowners paid no personal property taxes under the new system. (The Homestead Exemption remains a popular tax exemption in Louisiana.)

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

Automobile license fees were slashed. Rates on trucks were cut from $28 to $3, and rates on cars fell from $15 to $6. Personal property taxes on cars were eliminated. The average farmer saved $20 a year (or $240 today), and the average family saved $9 (or $108 today).

The poll tax was eliminated, allowing individuals to vote without paying the required fee of $2 (or $24 today) over two years. This tax, which was due every Christmas, prevented a whole class of citizens from participating in the elective process. When the tax was repealed, 278,000 people registered to vote for the first time, nearly doubling the size of the electorate.

Utility rates were reduced. Telephone rates fell 20 to 25 percent, saving the average family $12 a year (or $144 today). Electricity rates were also cut, saving the average family $27 a year (or $324 today).

To protect families from losing their homes during the Great Depression, Long created the Debt Moratorium Act, which stopped foreclosures and gave families a grace period to pay mortgages and settle debts, saving thousands of Louisiana families from losing their homes and lifetime investments in their property. When the state seized property due to failure to pay property taxes, families were allowed to regain it without paying back-taxes.

Long’s state banking policies and personal intervention prevented bank closures, saving thousands of Louisianians from financial losses. Of the nation’s 4,800 banks that collapsed between 1929 and 1932, only seven were in Louisiana.

- Previous page

- Healthcare

- Next page

- A New Democracy

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

How Did Long Pay for His Programs?

According to historian T. Harry Williams, "Louisiana was known as a state that levied remarkably few taxes ... not enough to support the kind of program Huey envisioned. The most lucrative one, the property tax, bore more heavily on the taxpayer of average or below-average means."

Long's ambitious road-building program was funded by bond measures that were voter-approved and backed by a gasoline tax. Long's education programs were funded by increasing the severance tax on natural resources extracted from the state by various industries based on quantity, which increased state revenue particularly from the oil industry. The funds for hospitals and other institutions came from taxing carbon black at one-half cent per pound.

Conversely, Huey slashed personal property taxes and fees, shifting the burden of government financing from the public to industry. Louisiana's total government operating costs (state and local) were $41.97 per capita - third-lowest among the 24 states that kept such records. During Long's governorship, taxes rose 2.2% compared with a national average of 4.7%.