Campaign for Governor

In 1928, Huey Long ran again for Louisiana governor, campaigning with the slogan, “Every man a king,” a phrase adopted from populist hero William Jennings Bryan. Huey’s revolutionary campaign and victory toppled the corrupt political establishment that had ruled since the French. Louisiana — and its politics — would never be the same.

Louisiana was run by the New Orleans-based political establishment, called the “Old Regulars,” who exercised total control of state government through the legislature and a network of local sheriffs and “courthouse rings.” These “machine politicians” enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with the wealthy planter class and large corporations and utilities, who were given free reign to profit off the state in return for their support.

Life in Louisiana

Life was hard in 1920s Louisiana, with little hope of advancement for a poor majority isolated by geography. In a state covering nearly 52,000 square miles, of which 16 percent is dominated by waterways, there existed only 300 miles of paved roads and three major bridges.

Sixty percent of the state’s two million citizens lived in rural conditions with only the bare necessities. Education was a luxury few could afford. Most white farmers had not completed the fourth grade, and nearly 240,000 adults could not read.

Meanwhile, Louisiana was widely regarded as the most backward state in the nation. Public education was virtually non-existent among the masses, and one in four adults could not read. Most families could not afford to purchase the textbooks required for their children to attend school. Dirt roads and abundant water hazards made travel and commerce difficult. The poll tax hindered the lower classes from voting, and the poor paid disproportionately high property taxes for state services they never received.

A brilliant orator, Long made hundreds of campaign speeches among rural voters, expressing a vision for a new Louisiana in which government would be responsive to the needs of its people. He promised Louisiana’s needy citizens good roads, bridges, free hospital care, free education, and lower property taxes.

Nicknames that Stuck

Rural audiences loved Huey’s sense of humor and the memorable nicknames he invented to poke fun at his opponents.

Favorites included “Turkey Head” Walmsley, “Whistle Britches” Rightor, “Shinola” Phelps, and “Feather Duster” Ransdell.

Long won the election by the largest margin in the state’s history, and his closest opponent refused to face him in a run-off. His support transcended the traditional Protestant-Catholic divide of Louisiana politics and replaced it with a new division between the “pro-Long” average citizens and the “anti-Longs” from the wealthy establishment that had been ousted from power. At Huey’s inauguration, more than 15,000 supporters flocked to the capital to see one of their own take the oath as governor.

Revolutionary Campaign Methods

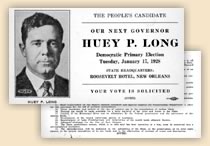

Courtesy of the Louisiana Political Museum & Hall of Fame

Huey’s revolutionary campaign methods transformed Louisiana politics. In his 1928 campaign for governor, he covered 15,000 miles on Louisiana's dirt roads and made 600 speeches. Poor voters felt privileged that a candidate would take the trouble to court them. At his own expense, he printed and distributed thousands of circulars – flyers that laid out in detail his reform agenda. Huey frequently resorted to standing on the top of his car to personally nail campaign posters high on telephone polls, where they could not be easily torn down by his opponents.

Huey attracted huge crowds with his fiery speeches, and his appearances became the talk of the state. A man of boundless energy, he pursued an exhaustive speaking schedule, often making five or more campaign stops a day. He captivated his audiences with his intellect and humor and could speak for hours without notes.

Having learned the value of showmanship during his salesman days, Huey dressed in his trademark white linen suits and presented himself as a country boy who never forgot his roots. He entertained crowds with a warm-up band, and then lobbed barbs at his “rascal” opponents to the delight of his fans.

In later campaigns, Huey used sound trucks to amplify his voice to the far reaches of the huge crowds he attracted, and he used radio speeches to reach a state-wide audience. When the state’s newspapers uniformly aligned against him and his reforms, Huey blanketed the state with his own position papers to explain his programs to the people. As governor, Huey labeled the press “the lyin’ newspapers” and started his own newspaper, The Louisiana Progress, to get his message out.

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

Huey reached nationwide audiences through radio broadcasts and a newspaper called The American Progress.

Always the music lover, Huey wrote a catchy campaign song, “Every Man a King”, that summarized his share-the-wealth philosophy: “Every man a king, for you can be a millionaire — but there's something belonging to others — there's enough for all people to share.”

- Previous page

- Entry Into Politics

- Next page

- Governor

Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Baton Rouge

Louisiana was stirring … The trappers and fishermen of the bayous, the Cajun farmers of the south and the redneck farmers of the hill parishes, the sharecroppers and tenants everywhere, and the laborers in the towns and the small businessmen in the villages … Now suddenly a champion had appeared to them, one who promised to lead them to a better life …”

— T. Harry Williams, Huey Long

The Evangeline Speech

Long's platform was summarized in a famous 1928 campaign speech delivered in St. Martinville, La., under the Evangeline Oak, the subject of a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

“…It is here under this oak where Evangeline waited for her lover, Gabriel, who never came. This oak is an immortal spot, made so by Longfellow's poem, but Evangeline is not the only one who has waited here in disappointment.

Where are the schools that you have waited for your children to have, that have never come?

Where are the roads and the highways that you send your money to build, that are no nearer now than ever before?

Where are the institutions to care for the sick and disabled?

Evangeline wept bitter tears in her disappointment, but it lasted only through one lifetime. Your tears in this country, around this oak, have lasted for generations. Give me the chance to dry the eyes of those who still weep here.”