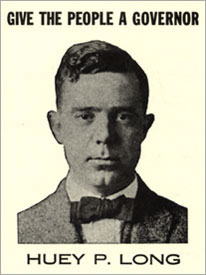

Entry Into Politics

Huey Long made a splash in Louisiana politics as a member of the Louisiana Railroad Commission, fighting corporate monopolies and reducing utility rates. By age 30, he was a major force in state politics and ran for governor in 1924, finishing a close third. It was the last political battle he would lose.

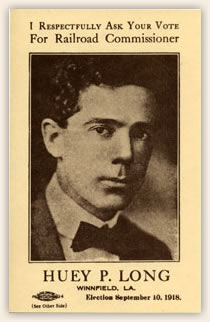

In 1918, Huey won a seat on the Louisiana Railroad Commission at age 25. Without the backing of the political establishment or business interests, he took his case straight to the people, blanketing his district with printed circulars attacking the corporate monopolies and delivering speeches in every town and crossroads in his district.

Campaign card from Huey Long's 1918 campaign for railroad commissioner. Click to read his campaign statement on the reverse, “Vote for a Principle.”

Courtesy of the Long family

He used his position on the commission (later renamed the Public Service Commission) to build a name for himself as a champion of the common man, fighting against utility rate increases and oil pipeline monopolies. His corporate opponents made an unsuccessful attempt to remove him from the commission.

Huey became chairman of the Public Service Commission in 1922 and won statewide acclaim when he sued the Cumberland Telephone Company for unjustly raising its rates by 20%, successfully arguing the case on appeal before the U.S. Supreme Court. The phone company was forced to send refund checks to 80,000 overcharged customers. Huey’s arguments on behalf of the state so impressed Chief Justice William Howard Taft, that he later described Huey as one of the best legal minds to appear before the Court.

The “Chattel” of the Corporations

In the 1920 election for governor, Huey supported “reformer” John M. Parker but later broke with Parker. Long was outraged that Parker allowed the Standard Oil legal department to write the state’s severance tax laws, which governed how much tax oil companies and other industries paid the state for extracting its resources.

In 1924, Huey made his first statewide bid for public office by running for governor at age 30. Huey mocked the outgoing governor and the ruling New Orleans political machine known as the “Old Regulars” as pawns of big business and Standard Oil, in particular. In an election dominated by race and the influence of the Ku Klux Klan, Huey refused to play the race card and instead campaigned on issues of economic equality. He ran a close third, missing the run-off election by less than 7,400 votes.

I’m beat. There should have been 100 for me and 1 against me. Forty percent of my country vote is lost in that box.”

— Huey Long, when the returns from the first ballot box from the country showed Huey beating his closest opponent for governor 60 to 1

Huey blamed his loss on the heavy rains the day before the election that had kept his rural supporters away from the polls. With less than 300 miles of paved roads in the entire state, frequent rains turned Louisiana’s dirt roads into thick mud, making travel impossible until the roads dried out.

Luckily for Huey, the sun was shining on Louisiana — and his campaign for governor — four years later.

- Previous page

- Early Career

- Next page

- Campaign for Governor

Courtesy of the Long family

I was born on a farm, am a common man, and my sympathies have always been with the masses. I am opposed by the privilege seekers and profiteers.”

Huey Long, in a campaign card for his 1918 campaign for railroad commissioner.