Education

Blessed with a brilliant mind and photographic memory, Huey Long easily circumvented the obstacles that prevented most rural children from attaining a formal education. Huey repeatedly skipped ahead — eventually passing the Louisiana bar exam at age 21 without a single diploma. Providing free education to all children would later become a hallmark of his political career.

Huey's mother, Caledonia, was determined that her nine children be well educated to achieve their fullest potential. There was no public school in Winnfield, so she home-schooled her children until more formal education became available.

Under the Kitchen Table

Caledonia’s schooling always included games and contests, plus recitation of poems and scripture. The little ones listened to their older siblings' lessons from under the kitchen table. Huey's younger brother, Governor Earl Long, chose to be buried on the exact spot of his happiest memories — the place where his mother's kitchen table once stood.

Huey and the youngest children would listen to their older siblings' lessons from underneath the kitchen table. The mainstay of their education was the Bible, in addition to penmanship, writing, math, history, classic literature and poetry.

For a few years, Huey’s father and some neighbors pooled their money to hire a teacher to conduct “subscription school” — a one-room school for children of various ages. Against his will, little Huey attended through the third reader.

Public Education

In the early 1900s, public schools were not available in most rural areas of Louisiana. Families of sufficient wealth could join together to hire a teacher – establishing “subscription schools” – but the vast majority of children were educated by their parents or not educated at all.

Even after public schools were established, students were required to buy their own textbooks, an expense that prohibited many poor families from sending their children to school. By 1920, only half of Louisiana’s school-aged children attended school. In 1928, Louisiana had the highest illiteracy rate in the nation – one in four adults could not read.

In 1903, at age 11, Huey started fourth grade in public school. Far ahead of his class, he was quite bored. Huey was a quick study and later convinced his teacher to let him skip seventh grade. In 1910, after completing the eleventh — and supposedly final — grade of school, a twelfth grade was added as a requirement for graduation. Huey circulated a petition against the additional year and was expelled. Consequently, he never officially graduated from high school. (He was posthumously awarded a high school diploma.)

Huey was an excellent debater in high school and won a scholarship to Louisiana State University as third prize in a statewide debating competition in Baton Rouge. However, he could not afford the textbooks or room and board to attend. Instead he became a traveling salesman. At age 17, he began touring the South for various companies, selling everything from cooking oil to patent medicines.

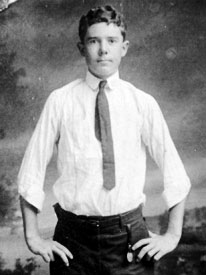

Huey (top right) in his school's group photograph.

Courtesy of the Long family

When sales jobs dried up due to the faltering economy, Huey’s mother saw an opportunity for her talented son to become a preacher as she had always hoped. She sent him to his older brother, George, in Shawnee, Oklahoma, to attend seminary classes at Oklahoma Baptist University. After one semester, Huey concluded that he did not have the gift for preaching and decided to give the University of Okalahoma Law School a try. Once there, he found campus politics more interesting than his classes and left school for a good sales job at the end of the term.

Huey's oldest brother, Julius, an attorney, counseled him to continue his law studies at Tulane University Law School in New Orleans. Julius gave him a detailed outline of which classes to take and enough money to last Huey and his bride, Rose, for one year. In 1915, after only one year at Tulane, Huey obtained permission to take a special oral bar exam before the examining committee. He passed easily and returned to Winnfield at age 21 to practice law.

Courtesy of the Long family

- Previous page

- Childhood

- Next page

- Early Career

“All Fixed Up”

Huey Visits the Big City

In 1909, Huey traveled with his high school debate team to a statewide competition in the capital, Baton Rouge, population 25,000.

Huey was dazzled by the modern conveniences he observed in the city – paved streets, electricity, and automobiles – and he realized how different life was in the city versus the country. He was also enamored by Louisiana State University, which he could not afford to attend.

When he returned home, Huey proclaimed that Baton Rouge “is all fixed up” and that one day he would fix up Winnfield, too.